Over the last month or so, I've given two free online talks for some literacy / dyslexia organizations. The first was on Function & Content Words, and the second was on Why Morphology Matters. Both were really well-attended, and I always feel so fortunate to see my study veterans show up. It moves me that people who probably already know everything I'm going to say still show up to hear it again.

I also love the new faces, and both of these workshops were full of so many new faces. Sometimes, the new faces grimaced in response to things I said, like "'Minimal unit of meaning' is a terrible definition for a morpheme," or "Stop teaching that. It's baloney." I mean, I get it. It's a big paradigm shift, when you first start studying the orthography for real. But that doesn't mean that syllable division isn't baloney. And you know what? The folks in these sessions were lovely about how damn hard it is to learn new things.

Both sessions had time for Q&A at the end, and most of the questions I fielded were familiar. For example, "What do you think of Words Their Way?" asked one participant.

"Oh," I responded, "I wrote a whole blog post about Words Their Way. It's called 'The Best Bag of Garbage in the Dump.'" People laughed nervously.

"It's actually a really good post," said a colleague. She's not wrong. I wrote it because I needed a place to send people who ask me what I think of some curriculum or other, because the curriculum is never the point. Besides, they all suck.

Another familiar question is about the proper age or grade level to begin teaching something, like function & content words, or morphology. This betrays a frustratingly broad misunderstanding about literacy instruction: it's never the case that you teach something once, and then you teach the next thing, and then the next thing. Rather, you are constantly spiraling back around to the same concepts, only at deeper levels. It's not the case, like phonics tends to think, that you teach all the phonology and then you start the morphology and then the etymology. You teach them all, interrelated, from the get-go. When Phombies say, "Well we don't just do phonics. We also do morphology," they are missing the point, because it's not both-and. It's all together. The interrelation is the point. So the answer to "When do we teach morphology / schwa / function words / homophones / suffix addition / whatever" is always "all the time, from the very beginning."

I also got what is perhaps the most frequent question from an OG / dyslexia audience. It's one that, for years, I had a hard time answering because I felt that I was on the defensive. It's a question that has several versions to it. One version is, "But don't you think that kids need to master their phonology first?" [No, and clearly most Phombies have not mastered theirs] or "But don't you think phonology is important?" [Yes – it comes in 4th, not 44th]. It is, in essence, the same question as the curriculum question, and that essence is "But how will I know that I am teaching all the things if I'm not phonicking?"

This time, the question came in this form, paraphrased: "Research shows that dyslexic children need systematic instruction. Do you agree with this, and how do you address that in your approach?"

I paused, because – while the asker assuredly had no malice – the question always sounds like a challenge to me. A whaddabout. A gotcha. I took a breath, and thought about it, and answered her. "Yes, I absolutely agree that all children – especially those who are struggling – need systematic instruction, which I define as study with an instructor who understands the system." I explained that when a teacher understands the system, she can use any curriculum and meet any child right where they need to be met.

Later that day, I got an email from one of the session's unfamiliar faces, brand new to this study.

"I wanted to tell you," she wrote, "I really enjoyed your session today. There were a lot of takeaways, but the one that will stick with me forever is when you were asked about dyslexic students needing systematic instruction, and you defined 'systematic instruction,' something all students need, in which the instructor understands the SYSTEM! It blew my mind, and added such a level of clarity. I definitely do not fully understand the system yet, but I am committed to working toward it, and absolutely understand the importance of doing so!

Well let me tell you, that comment made my day. To have made that specific impression on even one teacher in attendance will make a world of difference for dozens of kiddos, hundreds, perhaps thousands over a career (she's young!). I love that she's starting her study with that critical perspective, and I hope that other newbies caught those same feels.

The familiar faces, my longtime clients who sign up for every class, re-take classes, join my Facebook group, read this blog, and follow my work wherever they can, tell me all the time that it's good for them to hear things more than once. The other day, I had a lovely brunch with a local teacher who has been studying with me since shortly after I moved to Arizona in 2017. She's an amazing teacher and a dedicated student. Her notes from all my LEXinars are organized, and she frequently brings me great questions so I can help her help her kiddos. She told me over quiche and salad and tea, "It always helps to hear it again. I'm not there yet, but I'm getting there."

"You're not there yet?" I repeated. "None of us is. There's no 'there.' There's just further than you were before. Are you further than you were five years ago?" Of course the answer was a resounding Yes.

When she got home, she texted me some questions about one of her kiddos. "Can you think of how to help her w/<of> beyond its relationship w <off>? We are covering the floss rule in her group currently," she texted.

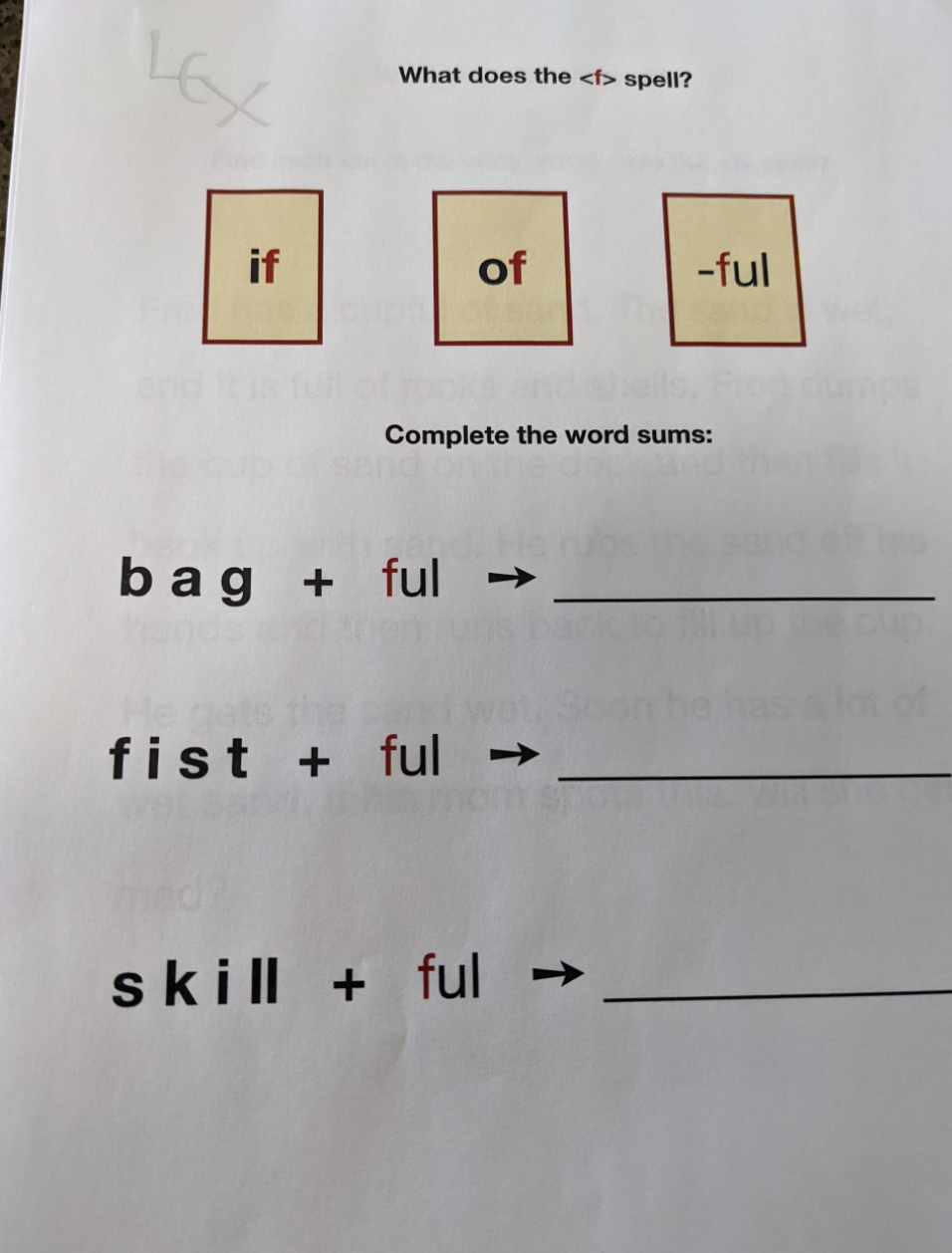

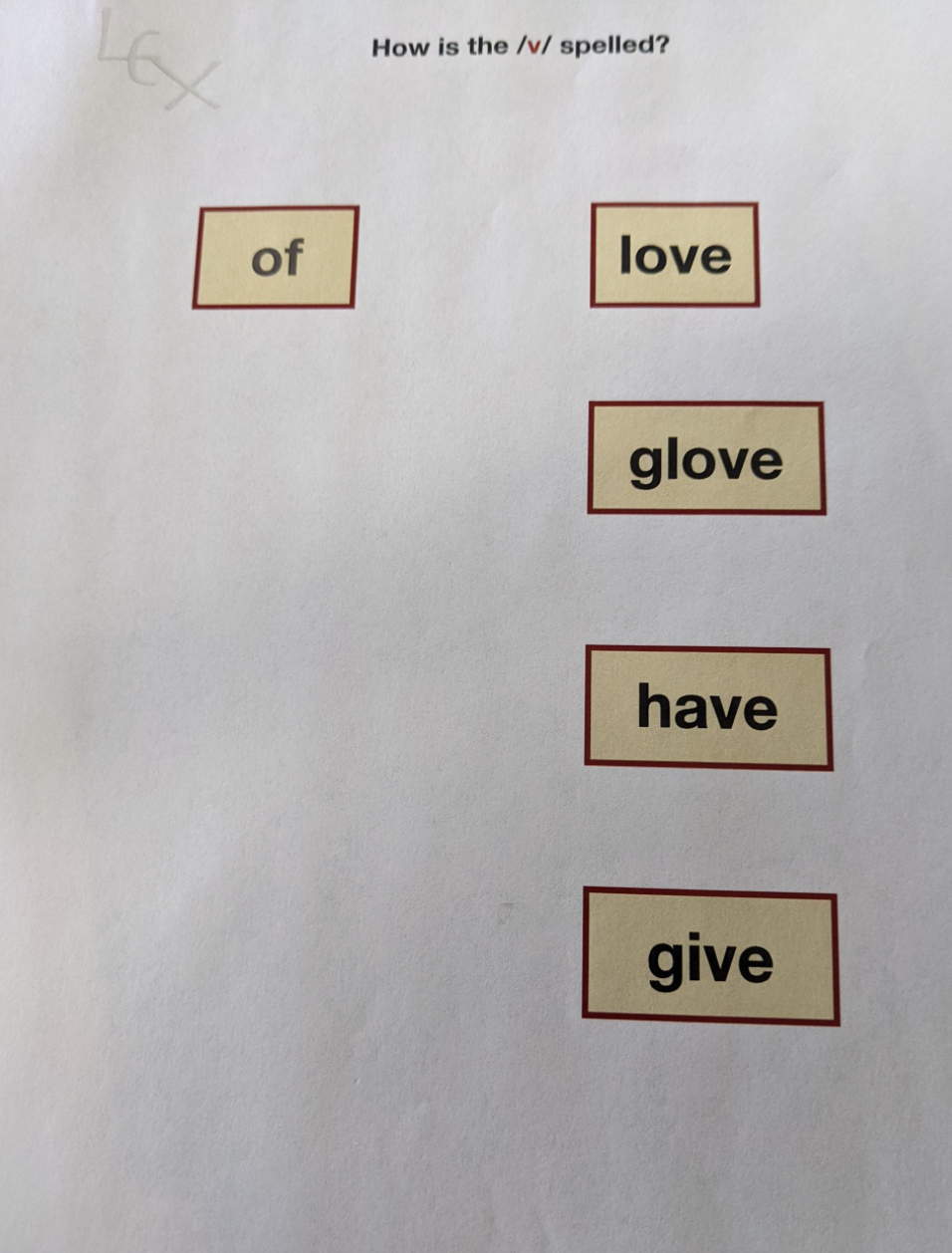

I responded: "We don't end words in <v>. We avoid <v> in function words. Study the similarity of [v] and [f]. We often pronounce 'of' like schwa alone. [As in Fourth ə July or piece ə cake.] 'Of' takes the smallest possible spelling. Compare it to 'love'. Why are they different? You don't have to do all of that. Just some thoughts to inform your thinking.

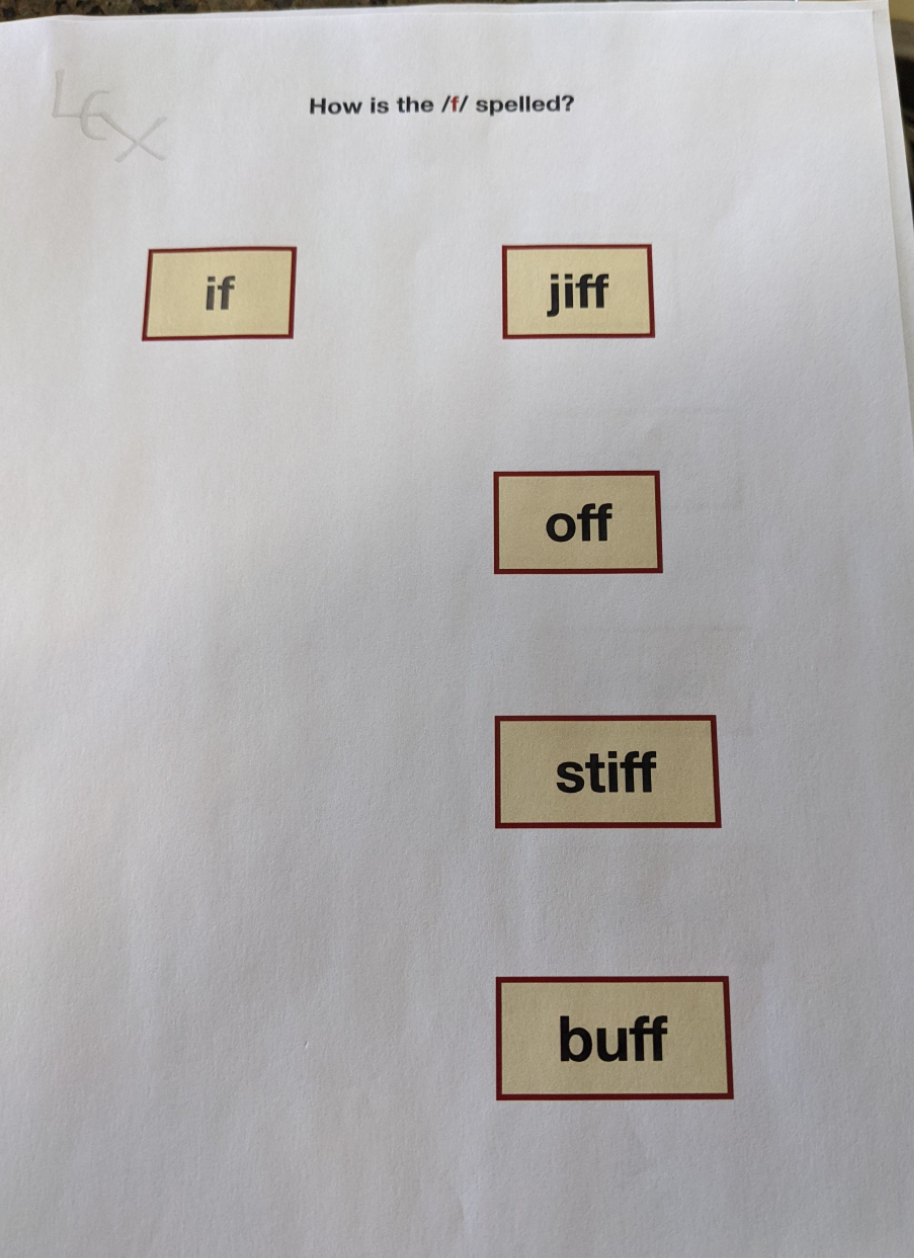

As we texted back and forth, she was going through her files and notes from my classes. Soon she texted me this photo:

"Is that mine?" I texted back, not noticing the LEX logo on it. "That's great!"

She responded with three more photos:

"Yes ma'am!" she responded. "It just keeps getting better and better."

I had no memory of creating this stuff, but apparently I did when I volunteered in her summer school classroom in 2018. In 2018, this content was brand new to this teacher; now, she's an old pro, and immediately recognized the value of these activities she had saved four years ago to the kiddo in front of her now. That's because she understands the system.

Just now, as I was copying the photos above from her texts to me, I got a new text from her: "The <of, love, glove,...> page, <of, off> work, and story identifying the sounds of <f> was super meaningful yesterday! We'll review and continue building on it next week."

See that? Review and continue building. The understanding of not ending a word in a <v>, of using an <o> when you can't use a <u>, of finding related words to make sense of spelling – those are all concepts that will come back around again and again and again. And that's not because she's got a magic curriculum, or because research told her to do something.

It's because that's the system, and this instructor understands it.